Charles Perrault's 1697 telling has long been the normative Western version of “Bluebeard”. A fabulously wealthy gentleman with a blue beard marries a young woman and sweeps her away to his fine country house. When he has to go away on business, he leaves his wife with a ring of keys; she can open any room in the house, except the small room on the lower floor. Of course, curiosity wins out and she opens the forbidden room, only to discover all of the corpses of Bluebeard's previous wives. Horrified, she drops the key into a pool of clotted blood. The bloodstain will not wash off, tipping her husband off to her discovery. Luckily, she is saved at the last minute by the arrival of her brothers, who cut Bluebeard down before he can kill her.

|

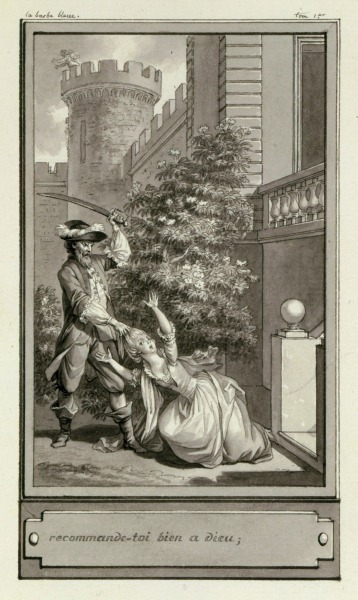

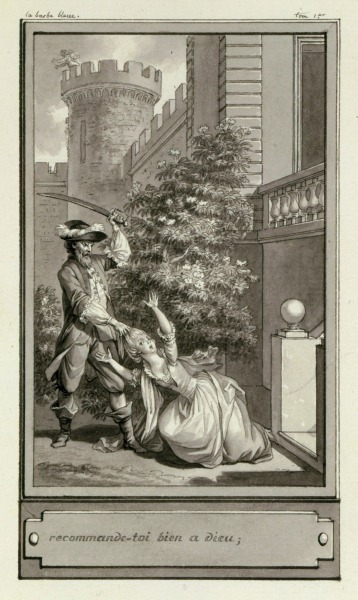

| "La Barbe Bleue", illustrated by Clement-Pierre Marillier |

Perrault tacks a moral onto the end of his story about

the dangers of female curiosity and wifely disobedience, curiously overlooking the fact that her

husband had an entire room filled with dead bodies. This isn’t unusual for Perrault; his instructional addenda are often absurdly irrelevant to the premises of the stories. In the case of “Bluebeard”,

such an interpretation has had a vigorous cultural cachet, though it is not the only way to consider the tale. As Maria Tatar observes, "Perrault’s story, by underscoring the heroine’s

kinship with certain literary, biblical, and mythical figures (most notably

Psyche, Eve, and Pandora), gives us a tale that willfully undermines a robust

folkloric tradition in which the heroine is a resourceful agent of her own

salvation. Rather than celebrating the courage and wisdom of Bluebeard’s wife

in discovering the dreadful truth about her husband’s murderous deeds, Perrault

and other tellers of the tale often cast aspersions on her for engaging in an

unruly act of insubordination." (The

Classic Fairy Tales, 141-142) Companion stories, such as the Grimm's "The Robber Bridegroom" and "Fitcher's Bird", notably center around a brave and clever heroine who not only saves herself, but also brings her homicidal fiance to justice on her own. Even a quick survey highlights the essential tension within these stories: is the woman a wilting victim at fault for her own persecution, or does she emerge as an admirable survivor?

|

| "The Robber Bridegroom", illustrated by Walter Crane |

By the late eighteenth century, longer prose fiction began to emerge from the "Bluebeard" tradition. Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto(1765) is generally credited with launching the Gothic novel in literature. By the end of the century, several similar books followed in its wake, including Ann Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho(1794) and Matthew Lewis's The Monk(1796), the latter often regarded as the most scandalous and titillating of the bunch. The books traded on atmospheric dread, un-dead monsters like vampires, and taboo sexuality, and so of course were wildly popular. By the early nineteenth century the market had been saturated to the point where it was ripe for parody, courtesy of Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey(1817). But even so, Gothic literature proved fertile ground for a few enduring masterpieces, chiefly Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre, which has never been out of print since its publication in 1847. Bronte's novel is noteworthy in many ways, not the least of which how it manages to contain all the requisite ingredients of a Gothic "Bluebeard" story while transcending typical limitations that accompany them. Told in the heroine's unique, determined voice, Jane Eyre emerges as a triumph of an individual will, both in fortune and in love. Not even the contents of the forbidden chamber are enough to break her spirit or ruin Jane's chances for marital happiness(significantly achieved when Mr. Rochester's secret is revealed and Thornfield Hall has burned to the ground). This is one of the reasons I find the 1944 Robert Stevenson film adaptation frustrating(notwithstanding Orson Welles as Mr. Rochester ); Jane becomes a wilting damsel-in-distress, as though the spirit of Perrault were being evoked instead of Charlotte Bronte.

|

| Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles in the 1944 Jane Eyre |

Joan Fontaine made a specialty of playing women who fell on the meeker end of the "Bluebeard" equation. In the 1940s, when there was a notable boom of female Gothic films, she appeared often in this capacity.The first, and arguably best, of these movies was Hitchcock's Rebecca(1940). Fontaine's presence as the mousy nameless new wife of the wealthy Maximillian de Winter(Lawrence Olivier) is counterbalanced to brilliant effect by Judith Anderson as the scary Mrs. Danvers, devoted to the memory of the eponymous first wife, who seems to exert influence on all the living while never being seen onscreen. The year after Fontaine received an Academy Award for playing almost the same role in another Hitchcock film, Suspicion, notable for a great scene with a glass of milk that may be poisoned and a ludicrous ending that negates all that came before(basically Bluebeard's wife being told that it was "all in her head"). Ingrid Bergman also received her first Best Actress Oscar for playing a paranoid wife, in George Cukor's Gaslight(1944), though in that film at least the malevolent husband doesn't escape blame; as he was played Charles Boyer, the odds of that were slim anyway.

|

| Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight |

|

| Judith Anderson and Joan Fontaine in Rebecca |

1948 brought along Fritz Lang's edition to the female Gothic film, Secret Beyond the Door. Starring Joan Bennett and Michael Redgrave, it is characterized by a bizarre and blatant artificiality(as many Lang movies are; they tend to cry out for a Brechtian response). When the wife finally enters the forbidden Room 7, she discovers that it is an exact replica of her own bedroom, intended to serve as the scene for her husband's next crime. It shouldn't be surprising that the film seeks to exonerate its Bluebeard with a hefty last-minute dose of the pseudo-psychoanalysis so in vogue at the time, however dramatically dissatisfying it renders the conclusion.

|

| Secret Beyond the Door. The door's design is standard German Expressionism |

This has been but a brief tour through the trajectory of "Bluebeard" and its Gothic offshoots, but it is by no means the end. As Marina Warner observes, "for women, the Bluebeard figure often embodies contradictory feelings about male sexuality, and consequently presents a challenge, a challenge they meet in variety of ways."(Once Upon a Time, 92) The past of this story would suggest that the present has several options. There is more than one way to survive and thrive.

Sources

The Classic Fairy Tales. Norton Critical Edition.

ed. Maria Tatar. W.W. Norton & Company. New York London. 1999. Print

Warner, Marina. Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale. Oxford University Press. 2014. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment